With a flourish of his hand, Rafael Petrosyan, formally attired in red patterned vest, black striped dress shirt and grey pinstriped suit slacks, bows.

“After you,” the sculptor says as he follows me into the Modern Art Foundry. “Two centuries ago, gentlemen bowed when ladies arrived. Ah, but it is no more.”

At the top of the linoleum-covered stairs, after a right and then a left, is what Rafael calls his cave. It’s one immaculate room doing double duty as two. There’s the main room, whose only furnishings are a table, an elfin refrigerator, an old desk chair on casters, a couple of clay models and a hot plate. Through the hastily closed curtain in the back is the bedroom, which is appointed only with a mattress.

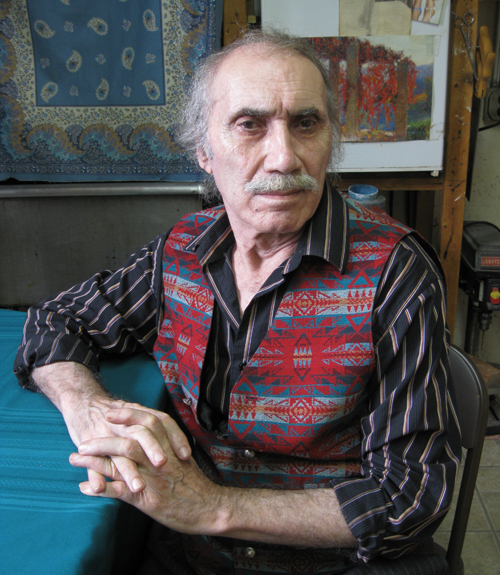

Photo by Nancy A. Ruhling

Rafael, the dapper and courtly sculptor.

As opera music wafts softly through the stale-cigar-scented air, Rafael, a wiry fellow with a bushy gray mustache, goes to the hallway to fetch a folding chair.

“Perhaps you would like a little red wine,” he says, holding up his fingers to indicate a demitasse-size drink. “In Armenia, it’s the way to start the day.”

Rafael left Armenia nearly four decades ago, but old customs die hard. He’s had his shot of wine already.

Photo by Nancy A. Ruhling

Rafael’s model for a monumental ode to America.

Ah, Armenia. It was hard to leave it, yes. But he had to. He’s only sorry he waited too long. He didn’t make it to New York until he was 47 years old.

“I came for freedom for my art,” the 80-year-old Rafael says. “I had a great position — I was a sculptor for the government, I had created 10 monuments, and I had had more than 40 exhibitions — but I could not do any extraordinary work. It was like I was a bird in a golden prison.”

But Rafael didn’t hesitate to give it all up. His father had been talking about coming to America ever since Rafael could remember. Rafael’s father had been wealthy, but when he refused to join the Communist Party, he was exiled to Leninakan, Russia. He became a beggar and was forced to do hard labor in an airplane factory.

Photo by Nancy A. Ruhling

At 18, Rafael copied Repin’s 1885 work “Ivan the Terrible and His Son.”

“My childhood was hell,” Rafael says. “We had no food, and I used to cry for bread. My father was only allowed to leave the factory on weekends. When he came home, he cried like a woman. His only pay was a bowl of soup each day that had two pieces of macaroni in it. The Communists killed him — he got TB working in the factory and died when I was only 14. I never forgave them for that.”

Art was the only thing that made Rafael happy. “I’m very romantic and sensitive,” he says, a flirtatious sparkle in his burnt-brown eyes. “I started drawing when I was young, and I was good at it. I also was good in sports — physically, I was like Hercules — but I was always looking at clouds. I liked drawing more.”

So it was that he graduated from the Yerevan Academy of Fine Arts in Armenia with a doctorate in sculpture, art history and design.

Photo by Nancy A. Ruhling

The tools of his trade.

Four days after he left his son and ex-wife in Armenia and arrived in Astoria, he got a job making reduced-scale art pieces for Alva Museum Replicas in Long Island City.

“Although I spoke Armenian, Russian and Georgian, I didn’t know any English other than ‘thank you’ and ‘sorry,'” says Rafael, who became a U.S. citizen in 1982. “I came to America like an idiot; even little children could speak better. Without language, I felt like a barbarian because language is the flag for human civilization.”

Ironically, the very freedom that Rafael sought almost proved his undoing. “In Russia, the government dictates to its artists, but it also supports them,” he says. “I had a free apartment and a free studio because of Communism. My dream was to come here and always be busy using my knowledge. It didn’t happen. At first, I was sorry and even depressed. But it was my fault, not America’s fault.”

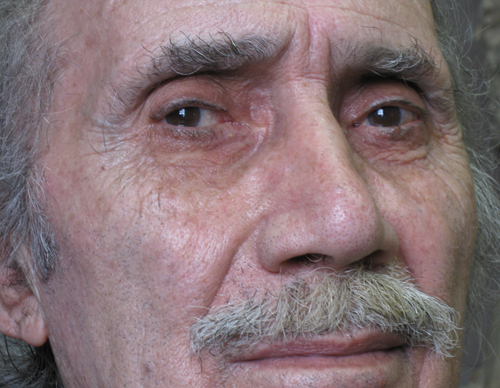

Photo by Nancy A. Ruhling

An up-close study of the sculptor.

A quarter-century ago, he began working for Modern Art Foundry. “In Russia, under Communism, nobody made any money,” he says. “When I got my first check in America, my employer thanked me for my good work, and I cried.”

In addition to fabricating the works of others, Rafael also works on his own pieces. His latest is a monument that he wants Armenian-Americans to present to the U.S. government. The bronze piece, which will rise 27 feet into the sky, shows Lady Liberty, draped in a Stars-and-Stripes Superman-like cape, sweeping up an Armenian family who have been nailed to a cross.

“In my mind, I’ve been working on this for 20 years,” says Rafael, as he works the pliant clay, which looks like butter-cream icing, on his life-size model of the family. “We have to thank America for helping the immigrants. If you’re born in this country and you’re still poor, it’s your own fault, because in America, all doors are open.”

Photo by Nancy A. Ruhling

A detail of one of Rafael’s later sculptures.

Rafael spends most of this time at the Modern Art Foundry, working on his monument and occasionally helping out in the factory with welding. The owners are like his family, and when he works late, as he does several times a week, he stays in his cave — the room above the factory.

“I have everything I need here,” he says, pointing out the shower and bathroom in the hallway. “Artists never retire. Michelangelo worked until he was 82, and so did Picasso. If I could get donations for my monument, I’d jump like a young man and finish it. It is the artist’s way to keep working.”

Photo by Nancy A. Ruhling

A portrait of the sculptor in his “cave” studio.

Once the monument is completed, Rafael has lots of other ideas he wants to take from clay to bronze. “In my brain, I have many projects,” he says. “But I don’t have hope because of the depression crisis. Nobody thinks of art at this time.”

The thought makes him sad, but his inner artist has been roused, at least for the moment.

“You have refreshed me,” he says. “Now I know I will not be forgotten.”

As I drive away, he smiles in the street and sends a solitary salute.

Nancy A. Ruhling may be reached at Nruhling@gmail.com.

Copyright 2010 by Nancy A. Ruhling