There’s no bookstore in the Ditmars section of Astoria. We don’t need one. Harry puts the words out on the street.

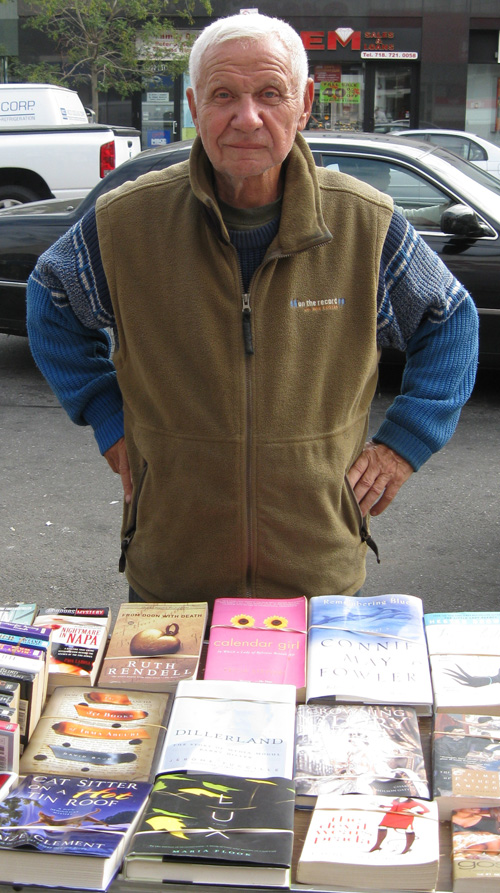

Harry – we all know him as Harry, but for the record, his full name is Harry Fiegelson – is the 82-year-old World War II veteran who sets up a bookstand by the subway stop at 31st Street and Ditmars Boulevard. He sells his hand-picked selections for $1.50 each.

“We’ve got books today,” he repeats over and over like an old-time carnival barker to all who pass.

“Hey, Harry, what have you got today?” asks a man in a tie as he peruses the titles that range from Calendar Girls and The Devil Wears Prada to Ayn Rand’s We the Living. “I want something that keeps my interest – I don’t want anything boring.”

Photo by Nancy A. Ruhling

From his street stand, Harry reads the crowd.

Harry searches through the used paperbacks, some of which are bound with rubber bands, and hands him one of Jonathan Kellerman’s Alex Delaware detective books. “His wife, Faye Kellerman, is better, but you’ll like this one,” Harry tells him as he pockets the money.

Harry’s bookstand has been in the same spot for nearly a quarter century, and he sets up shop every day when the weather is good. He rises at 3:30 a.m., packs two carts full of books from his collection of 500-plus volumes and wheels them, one by one, the half mile from his basement apartment starting at 5:30 a.m. Then he returns for the trio of aluminum fold-up tables and officially opens for business at 7 a.m., in time for the first crowd of commuters.

“I used to sit on the bench here reading, and one day I brought some books and spread them out on the ground, and people started buying them,” he says. “Ever since, I’ve been spending my free time searching church sales and thrift shops for used books.”

Harry’s always been a big reader – “I like everything from romance to mysteries, but no science fiction” – and his life story is a page-turner. “I’m not important,” he insists. “I can’t think of anybody other than myself who would be interested.”

It’s a good thing, then, that’s he’s not writing his own story, because it never would be told.

Harry grew up in Manhattan and spent his early teens waiting to get into the Big War. As soon as he turned 17, he joined the Navy “because I wanted to do something for my country.” With his close-cropped halo of silver hair and penetrating sapphire eyes, he still looks like a military man. Even after more than six decades, he’s ill at ease when he’s standing at ease.

He became a seaman second class and served two years. “I never killed anyone, thank God, but I did have a lot of adventures,” he says. “I saw a lot of things you can’t believe.”

There was the time on the tanker when he fell overboard with a line tied around his waist and ended up in the hospital, where he had an emergency appendectomy. He almost found buried treasure – “we missed it in the water by about a day; it was a Japanese soldier who had sunk the chest filled with diamonds” – and watched the shore of Nagasaki from a landing boat two days after the atomic bomb was dropped.

“I could see mothers with babies in their arms standing there ready to jump into the sea to commit suicide,” he says, his eyes saddening as they look back through time. “I didn’t see anyone jump, but it was clear that that’s what they were going to do.”

He also had a close call with a kamikaze pilot who flew over his ship in Yokosuka, Japan. “He was so close – about four to five feet, about the same distance from here to the Jolson liquor store – that I could see his face,” Harry says. “I’ll never forget that face. He flew over my head and did a belly-wop and bombed the ship next to me.”

Harry was at sea in Japan when the surrender was signed aboard the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay. “I was three blocks away from that ship,” he says.

After his tour of duty, he returned to the Big Apple. For a couple of years, he worked as a glazer’s helper, then he got a maintenance job with the United Nations, where his primary function was to move furniture.

“I met many famous people there, including Eleanor Roosevelt,” he says. “I remember overhearing two guards for Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld talking. It was 1961. One guy had a date with a girl, so the other guy switched shifts with him so he could have the next day off. The guy who switched to cover for his friend and Hammarskjöld were killed the next day when their plane crashed. The scenario always stuck with me.”

Photo by Nancy A. Ruhling

In Harry’s world, it’s word of mouth that makes the sale.

When he was 55, Harry up and retired. “It was a cold day, and I had to get up early, and I just didn’t want to do it any more,” he says.

He moved to Astoria to be near his niece. “I’ve only been here 25 years,” he says in apology. “As soon as I did that, she moved to Long Island.”

Harry cocks his eyebrow. Of all the bad luck! He’s still amazed at her audacious action.

The sales day is over, and Harry begins packing up for the triple trip back home. A customer drops off a plastic bag of books for him, so his load won’t be any lighter. Tonight, he’ll watch a little TV and finish a couple more chapters in the spy novel he’s reading before turning out the lights and turning in at 8:30.

“If I weren’t here selling, I’d be reading more,” he says. “But I like to talk to the people. It gives me something to do.”

Nancy A. Ruhling may be reached at Nruhling@gmail.com.

Copyright 2009 by Nancy A. Ruhling