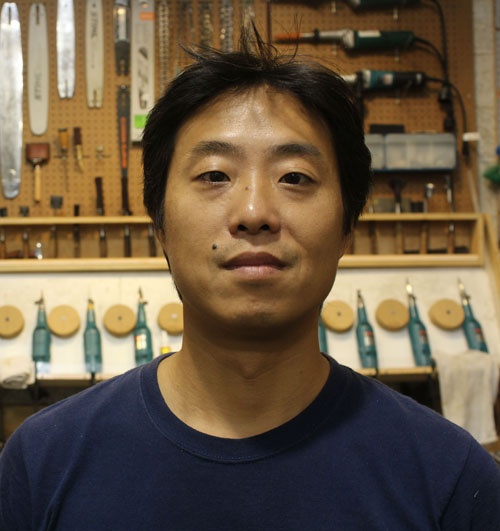

It happened many moons ago, but when Shintaro Okamoto opens the door of the walk-in freezer and sees the tiger’s head, he remembers the swan.

It was winter in Alaska, and Anchorage was as frozen as a pack of Popsicles when his father, Takeo, took Shintaro out to the lake to cut out the block of ice to sculpt the cygnet.

Shintaro wasn’t even a teenager when this occurred, and he had no idea that that simple swan would change the course of his life, leading him to open the ice sculpture studio that proudly bears his family name.

Photo by Nancy A. Ruhling

Shintaro’s the owner of Okamoto Studio.

Shintaro, who has raven hair and Popeye arms, stares into the icy eyes of the tiger and strokes its frozen fur.

“Ice is a fantastic, malleable material that is underappreciated and underused,” he says. “It’s special because it’s so tangibly, visibly clear that it’s melting away that it makes people more aware of the present — that’s where the poetry resides. It’s not sad to see the sculptures go away, it’s an exercise in letting go.”

Photo by Nancy A. Ruhling

The outside of the studio is defined by its ice cube-like windows.

He puts the tiger’s head back in cold storage and warms up to the past. Shintaro spent the first nine years of his life in Fukuoka, Japan. It was Takeo who got the idea to settle his wife and two sons in Alaska, where he landed a job as a sushi chef. During his training, he took a class in ice sculpting.

“We were latchkey kids,” Shintaro says. “And we grew up fast. My parents, who started their jobs immediately after we arrived in America, worked until midnight. I was scared — I used to cry on my little brother’s lap until they came home.”

Photo by Nancy A. Ruhling

Shintaro, a native of Japan, grew up in Alaska.

Shintaro didn’t know how to speak English, so he let his artwork be his spokesman.

During lunch break at elementary school, he drew pictures of animals on the chalkboard, and his classmates crowded around him.

Photo by Nancy A. Ruhling

Shintaro’s in-studio shrine to his father, Takeo.

After he won an art contest, his teachers fostered his talent, sending him to study with a wildlife artist and enrolling him in a night course in painting at a community college.

“I was the only kid there,” he says. “I used to do my homework from middle school during breaks.”

Photo by Nancy A. Ruhling

Shintaro and his father opened the studio in 2004.

After taking a class in nude drawing, he became fascinated with physiology and spent time watching a surgeon operate so he could make drawings to help the doctor’s prospective patients understand the procedures.

All the while, he and his father were winning ice sculpture competitions.

That ended when Shintaro enrolled as a pre-med student at Brown University. His major was fine arts.

Photo by Nancy A. Ruhling

From Buddhas to stuffed caribou heads, Shintaro is inspired by many things.

“Every day, it was a struggle between my right brain and my left brain,” he says. “I couldn’t decide whether to devote myself to medicine or to art. Then one day I realized that I needed to be making art.”

But he also needed to be making money; he had married and moved to New York City so his wife could attend Columbia law school. While he continued to make art, he did odd jobs.

Photo by Nancy A. Ruhling

Shintaro at one of the ice-making machines.

In 2000, the family, which now included two daughters, moved to American Samoa, where his wife clerked for a judge. A year later, when they returned, Shintaro began working on a master’s in fine art in painting at Hunter College.

“I started asking, ‘What will I do?’ My wife, after having our third daughter, hated her law-firm job and wanted a change. And my father was itching to try something different.”

Photo by Nancy A. Ruhling

From sketches cometh Shintaro’s ice sculptures.

The something different became the Okamoto Studio, which, since its opening in 2004, has made crystal-clear ice art for events at venerable venues like The Plaza Hotel, The Waldorf Astoria and The Ritz-Carlton. Okamoto Studio’s ice sculptures, which run from $500 to $100,000, also have had starring roles at Fashion Week, official Emmy Awards parties and high-profile film premieres.

Photo by Nancy A. Ruhling

Simple patterns encased in blocks of ice wait to be sculpted.

Shintaro makes ice sculpting sound simple. After he creates a design in consultation with the client, he uses an electric chainsaw to carve the rough form, which is shaped with flat chisels, chippers and saws. He draws the finishing details with electric drills that have custom bits designed specifically for this art. For flat works like logos, he custom prints the design and embeds it in the ice block before sculpting around it. He wraps the finished works in blankets and shrink wrap and transports them via freezer, refrigerator or even box trucks.

“We use incredible, beautiful, dangerous tools,” Shintaro says. “We don’t carve in the freezer — it’s too cold, so once we start, it’s a go, go, go nonstop, one-shot process because ice is a changing material.”

Photo by Nancy A. Ruhling

Shintaro at the eyes of the tiger.

Some works, like the 8-foot-high half-scale replica of Central Park’s iconic Alice in Wonderland statue, are made in pieces that are assembled on site; water is used to bind them together.

When an ice sculpture melts, it weeps. The studio, too, has had its share of tears. Shintaro’s wife no longer helps out because they are divorced. And Takeo, who served as master sculptor, passed away this year. Shintaro has set up a small shrine to him in the studio.

Photo by Nancy A. Ruhling

Shintaro hopes someday to return to his painting studio.

“I’m always here,” Shintaro says. “I’m still trying to go back to my painting studio, but I’ve created a monster. I’m so obsessed with sharing and showcasing our work that that’s what keeps me going.”

He hesitates to confirm that he’s at the studio seven days a week. “The people who love me hate me for being here more than I should,” he says.

As assistant comes in. He leaves to brief her on the latest sculpture.

Nancy A. Ruhling may be reached at Nruhling@gmail.com.

Copyright 2012 by Nancy A. Ruhling