The painting, a brooding tattoo of black and white shapes flowing together like a raging river, is wrapped in a cage of thin clear plastic. Anthony Cardillo releases it and holds it in front of his body like a warrior’s shield.

Photo by Nancy A. Ruhling

Anthony’s art gets him through life.

Wave of Emotion expresses what Anthony felt like when he was painting it. Happy. Sad. Scared. Depressed. Angry. The painfully personal painting possesses a precarious off-kilter balance that slyly shifts with each viewing.

“It glows,” Anthony says, “in the dark.”

It’s a good thing Anthony has a talent for art. He’s always needed a safe way to survive.

He opens a folder of drawings he made in his teens. Page after page, they tell his story better than he ever could.

Photo by Nancy A. Ruhling

Anthony holding Wave of Emotion.

An only child, Anthony was pretty much left to fend for himself since the beginning. His mother, a diabetic drug abuser, and his father, an alcoholic, divorced when he was 5. At 7, he was diagnosed with diabetes.

“I had to wear a bracelet and give myself shots,” says Anthony, who has the chubby cheeks of a boy and the blazing tattoos of a biker. “I was constantly reminded that I was different from the other kids at school.”

He and his mother lived in Norwalk, Conn., on her scant welfare check. She didn’t make it to Anthony’s 12th birthday.

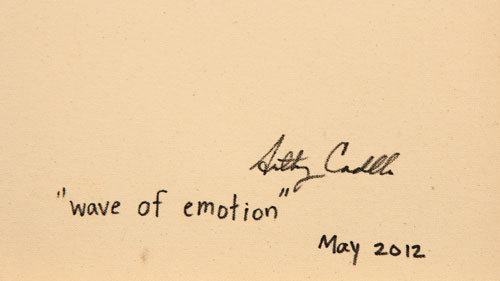

Photo by Nancy A. Ruhling

Anthony’s signature signature.

“One morning, her alarm clock rang, and she didn’t shut it off,” Anthony says. “I found her dead in her bed.”

Anthony sketched his grief away.

“I also started experimenting with drugs, especially coke,” he says. “As I got older, my drug use intensified.”

Photo by Nancy A. Ruhling

His eyes read his mind.

After living a short time with his grandparents, Anthony was taken in by his father, who moved him to Fort Lee, N.J.

“It was hard because I had to leave my friends,” he says.

Anthony drew instead of crying.

When he was 17, his father remarried, and the family came to Astoria. By this time, Anthony knew he was destined to be an artist and started working his way through the School of Visual Arts.

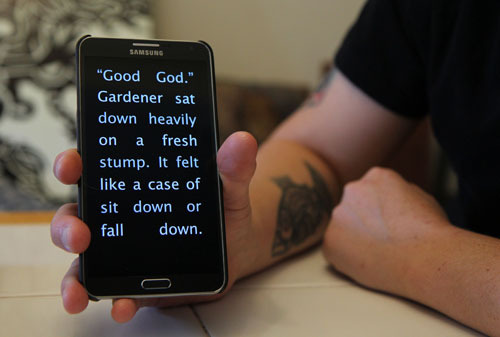

Photo by Nancy A. Ruhling

Anthony can only read very large type.

“I always drew in black and white,” he says. “I never saw the world any other way.”

Daydreams kept calling him away, so he didn’t last long in the classroom. But he kept drawing strength from his art.

When he was 18, he did a three-month stint in a rehab center in Virginia.

For diabetes. Not drugs.

Photo by Nancy A. Ruhling

A sculptural work by Anthony.

“My blood-sugar level was so high that I was having blackouts and falling down,” he says.

It was there, with other kids who had medical problems, that Anthony found a jagged fragment of happiness.

“There was one girl there who never talked,” he says. “But I got her to do it. I was so good at working with the kids that they offered me a job.”

Photo by Nancy A. Ruhling

Pixie, one of Anthony’s four cats.

Instead, he apprenticed as a carpenter, scaling skyscrapers. He loved being up in the air.

But his blackouts returned. He had inoperable malignant germonia tumors in his brain. The chemo treatments kept him hospitalized for almost a year.

“I was very angry and wanted to know why God was doing this to me,” he says. “I was drinking heavily and doing drugs, mostly coke, to try to escape my life, but it was like putting a Band-Aid on a mortal wound.”

Photo by Nancy A. Ruhling

He’s optimistic about his future.

Anthony stopped his destructive habits, but more tumors were found on his brain. The radiation treatments, and other medical factors, left him legally blind.

“This was — and is — emotionally very hard for me,” he says. “I can’t read unless the words are magnified, I can’t drive at night, and I can’t play baseball or football.”

Two years ago, his myriad medical problems, which also include hearing loss and ringing in the ears, forced Anthony to quit construction. Now, at 38, he relies on disability and Social Security.

“I try to focus on things I can do, not things I cannot do,” he says. “I’ve returned to art.”

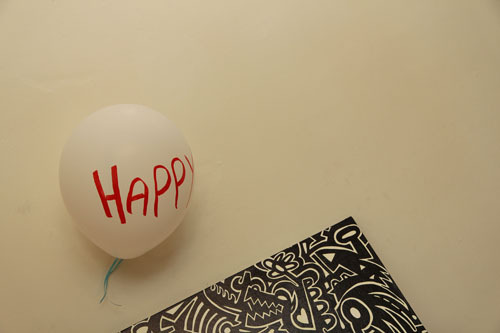

Photo by Nancy A. Ruhling

How Anthony tries to make everyone feel.

It’s painstakingly difficult for Anthony to paint. Although he can’t see the canvas clearly — he has to use a magnifying glass or wear extra-strength eyeglasses — his inner vision guides his hand.

“I don’t make sketches,” he says. “The ideas spring from my mind.”

Anthony doesn’t deny that he has had some dark days. More times than he would like to admit, he thought about dying.

But that, he stresses, is all in the past. He’s not on his own any more. He remains in close contact with his father, stepmother and stepsister, and he got married a year ago.

Photo by Nancy A. Ruhling

A detail of Bloom, Anthony’s latest work.

“I face challenges straight on and don’t go around them,” he says.

That’s why he has put all his energies back into painting.

“Whatever I’ve lost physically, I’ve gained something in return,” he says. “I have choices. I can see things in a negative light or positive light, and I choose positive.”

His latest canvas, which is nearly as tall as he is, features a burst of color in the center of its signature black and white background.

Anthony calls it Bloom.

Nancy A. Ruhling may be reached at Nruhling@gmail.com, nruhling on Instagram.

Copyright 2015 by Nancy A. Ruhling