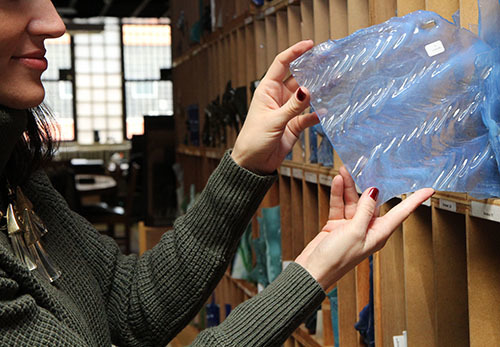

From the more than 250,000 pieces of Tiffany art glass at The Neustadt, Lindsy Parrott pulls out a rippled cream-colored sheet and holds it up to the light.

It comes luminously alive, its drapery-fold waves forming a shining sea of shadows.

“It’s my favorite piece,” says Lindsy, the director/curator of the museum. “It’s exceptionally beautiful.”

Brilliant. Gorgeous. Dazzling.

These are the adjectives she utters as she walks among the vertical shelves of opalescent sheet glass, mosaics and pressed-glass jewels that are stored in the 2,500-square-foot archives in Long Island City.

“The materials Tiffany used were incredibly artistic,” she says. “They enhanced his designs.”

If The Neustadt’s glittering glass is alluring, the story of its salvation is equally enchanting.

It was Dr. Egon Neustadt and his wife, Hildegard, who amassed the glass – and a colossal companion collection of Louis Comfort Tiffany windows, lamps and desk sets that they eventually donated to the Queens Museum and the New-York Historical Society.

They paid $12.50 for their first daffodil lamp in 1935, about five years after Tiffany’s Corona factory wound down production.

At that time, Tiffany was out of style, the lamp was second hand, and Neustadts were delighted to display their find in their Flushing home even though its bargain-basement price broke their budget.

The Neustadts were ahead of their time: Today, the lamp that the doctor’s friends didn’t like when they saw it on his desk sells for $33,000 to $60,000.

As the decades passed, the Neustadts, Austrian immigrants who were enamored of all things American, continued to collect, and in 1967 they purchased the treasure trove of factory leftovers that comprise the museum’s holdings.

“The glass was in cardboard boxes all jumbled up,” Lindsy says. “Each piece was separated first by size then type and color. We are still in the process of getting it organized.”

Lindsy, who joined the museum 14 years ago, shares the Neustadts’ exuberant enthusiasm for Tiffany’s designs.

Born and raised in West Palm Beach, Lindsy, slender and stylish, has always had artistic aspirations.

“My parents loved art and took my younger sister and me to museums,” she says. “I always wanted to work in one. By high school, I was making ceramics.”

While she was earning a degree in art history at the University of Central Florida, she spent her summers working for the Norton Museum of Art in West Palm Beach.

In her junior year, she took a part-time job in Winter Park at the Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art, which has the world’s most comprehensive Tiffany collection.

“I had never seen any Tiffany windows in person,” she says as she runs her hand over a piece of textured glass. “When I saw Feeding the Flamingos, I was immediately hooked. I was captivated by how sculptural and sensual the drapery glass was.”

So entranced was she by the works of Tiffany that after working there full time for three years, she moved to Washington, D.C. to earn a master’s degree in the history of decorative arts through the Parsons School of Design in conjunction with the Smithsonian Institution.

“I entered knowing I wanted to pursue Tiffany,” she says. “I wrote my thesis on Tiffany’s Favrile pottery. My thesis adviser was involved with the Neustadt.”

Lindsy, who joined the Neustadt in 2003, likens herself to a history detective who, glass piece by glass piece, puts together Tiffany’s story.

“It’s exciting to have insights into Tiffany’s working process,” she says. “The thing that keeps me involved is the number of people who were in production. Tiffany had to hire chemists to develop the recipes and people to mix the batches. There were glass makers, designers, selectors and cutters. There were pattern makers, and there were people who wrapped foil around the glass, people who cast the bronze bases, people who soldered the glass and people who wired the lamps.”

Lindsy, who does not have any Tiffany of her own, is one of only three staffers at the nonprofit museum.

She does a variety of tasks that range from buying office supplies to writing catalogs and selecting glass for shows like A Passion for Tiffany Lamps at the Queens Museum.

Lindsy, who puts in 10-hour days and the occasional all-nighter, hopes her work brings the world a deeper appreciation of Tiffany’s work.

She has won over at least one person: Jackson, her 8-year-old son.

“He loves to look at the glass jewels and gives his friends little tours,” she says. “When we go to the Queens Museum, he points out special features of the lamps.”

The Neustadt has traveling exhibitions, and Lindsy is hoping to create more collaborations that will put Tiffany in the public eye.

“There’s still so much to do,” she says and smiles.

Nancy A. Ruhling may be reached at Nruhling@gmail.com; @nancyruhling on Twitter; nruhling on Instagram, nancyruhling.com, astoriacharacters.com.

Copyright 2017 by Nancy A. Ruhling