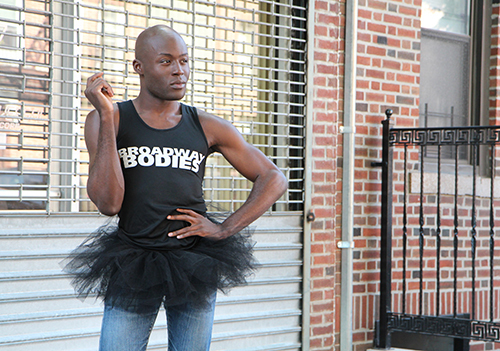

“Before I do anything else, I have to put on my tutu,” says Alistair Williams.

He drops his canvas gym bag on a chair outside Madame Sou Sou Café on 33rd Street, which is where he usually hangs his tutu.

Like a magician with a rabbit, he pulls out a scrunched-up circle of black tulle.

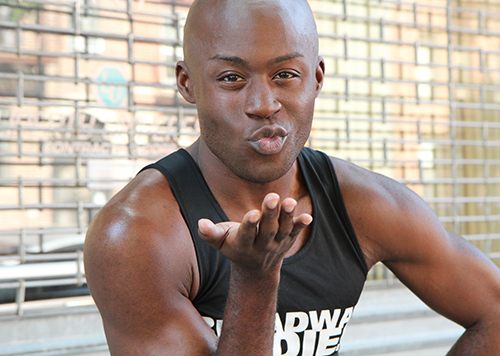

Alistair, tall and lean in jean shorts, Yankees cap and sleeveless Broadway Bodies T, slips it over his big, black Nike Air Force 180s and does a little dance.

Ah, that’s better.

There was a time, and it wasn’t all that long ago, when Alistair would not have dared don the tutu on the street or even in the privacy of his own closet.

Once he moved to Astoria, though, he decided to unleash his brawny bald ballerina.

“I put it on and nobody even paid any attention,” he says, grinning. “This was a new experience for a gay kid who grew up in a Christian church.”

The church played a large role in his life. He was born into the Pentecostal Apostolic Church, but the family switched when his mother became the pastor of an American Baptist church in Union, New Jersey, his hometown.

That’s how Alistair became director of the choir when he was 4.

“I was always singing and dancing,” he says. “My mother took me to choir practice, and when the choir director didn’t meet my standards, I thought I could do it better, so I started moving my arms around obnoxiously. When she saw me doing this in the corner, she asked me if could do it in the center of the room instead. I told her that of course I could, and they put me up on a chair.”

By 8, Alistair was taking voice lessons, and by 16, which he says was far too late, he was in ballet class.

Singing and dancing were an escape from church and school, where Alistair was teased and tormented.

“I was sitting through sermons that said God doesn’t make faggots,” he says. “Education for me was brutal. At that time in Union, being a gay, flamboyant black male was still an anomaly that many weren’t able to understand – myself included.”

Ashamed and guilty that he was gay, he made an effort to straighten himself out when he rejoined the Pentecostal church at 19 by electing to undergo conversion therapy.

“I was determined to live my life as a heterosexual man,” he says. “The first spiritual exorcism didn’t work, so I did it a second time. I used to joke that I was so gay that they had to do a follow up.”

While the church spurned him, his mother stood by him.

“I came out to her when I was 17,” he says. “She told me that she would love me whether I was gay, straight or a monster. Telling her I was gay was the easiest thing I had ever done; at 27, telling her I was leaving the church was the hardest thing I had ever done.”

Alistair sang and danced his way through public high school, where musical theatre was just as popular as football.

“The arts community was incredibly accepting,” he says. “And my work on stage gave the general public the opportunity to finally make sense of me. The ability to control the audiences’ laughter and applause was so empowering for a gay kid who was the butt of jokes offstage.”

After trying community college, starting his own business and working for a charter school, Alistair decided to study acting at Rutgers University. He was 24.

“I was miserable until I got there,” he says.

While taking classes, he worked full time as the assistant director of the school’s community arts department then became the director of musical theater of the Rutgers division.

“I left after five years because I felt I was losing my youth – my 20s were gone,” says Alistair, who is 31. “I wanted to find my passion.”

He didn’t have to look long or go far: He landed a job with Broadway Bodies in Chelsea and recently became its executive director.

“We offer instructional entertainment,” he says, adding that when he teaches classes, he’s in glitter, makeup and, of course, the tutu. “It’s like a curated dance party where you can express, create and explore who you are in a shame-free environment. It’s all about the joy of movement. Fitness is a byproduct.”

Alistair is hoping to set up stage in Astoria soon: He’s working on putting on a version of Broadway Bodies at Icon Bar on 33rd Street.

“I wanted to bring this shame-free philosophy, which is the pillar of our program, to the gay community,” he says.

Someday, he’s like to expand upon that idea, creating his own brand.

“I want to be the new Richard Simmons,” he says. “I want his positive, uplifting, eccentric voice to come alive again, especially in these times.”

But he acknowledges that he still has a lot of things to work out.

He hasn’t, for instance, found a church where he fits in.

“I miss the depth of the community and the people transforming or desiring to transform,” he says. “But living in Astoria feels like home.”

And Broadway Bodies aside, he hasn’t committed to a formal exercise program.

“I have a gym membership, but I’m still intimidated about going, so I don’t,” he says. “I feel I don’t measure up to all the men around me.”

He makes a slight adjustment to his tutu.

Nancy A. Ruhling may be reached at Nruhling@gmail.com; @nancyruhling on Twitter; nruhling on Instagram, nancyruhling.com, astoriacharacters.com.

Copyright 2017 by Nancy A. Ruhling